New Pre-Print about Enhanced Weathering: It’s Not Just the Rock—It’s the Soil (And it holds on tight)

Based on the large dataset from our greenhouse experiments we have written an extensive paper about alkalinity and cation retention in Enhanced Weathering (EW) projects over recent months. Just now our submission to EGUsphere appeared as a preprint!

“Soil processes govern alkalinity and cation retention in enhanced weathering for carbon dioxide removal” (Hammes et al., submitted).

It’s the result of five years of work, including two full years of experiments in what we believe is the world’s largest greenhouse setup for enhanced weathering (EW). In this paper, we zoom in on one core question:

When we add rock dust to soils, where do the weathering products actually go – into leachate as alkalinity, or into the soil itself?

And what does that mean for real, verifiable CO₂ removal?

A note of caution: Our experiments are obviously limited to the set of soils (all from Germany), the feedstocks that we selected and the limited time (in EW timescale) of 2 years. The results may not be representative of all possible combinations for rocks suitable for weathering and soils from all over the world. Your mileage will vary. But still, the results are pointing to soil processes that need much more scientific attention.

What we did in the greenhouse

In this study, we focused on alkalinity in leachate water and cation storage in soils:

In short, we:

Ran a two‑year greenhouse experiment, where this paper focuses on 4 soil types (7 soil batches) and a set of 13 rocks and industrial feedstocks (mafic (basanite), ultramafic (peridotite), carbonate-bearing (metabasalt), carbonate-rich (limestone), highly alkaline industrial by-product (steel slag), glacial sediment, etc.).

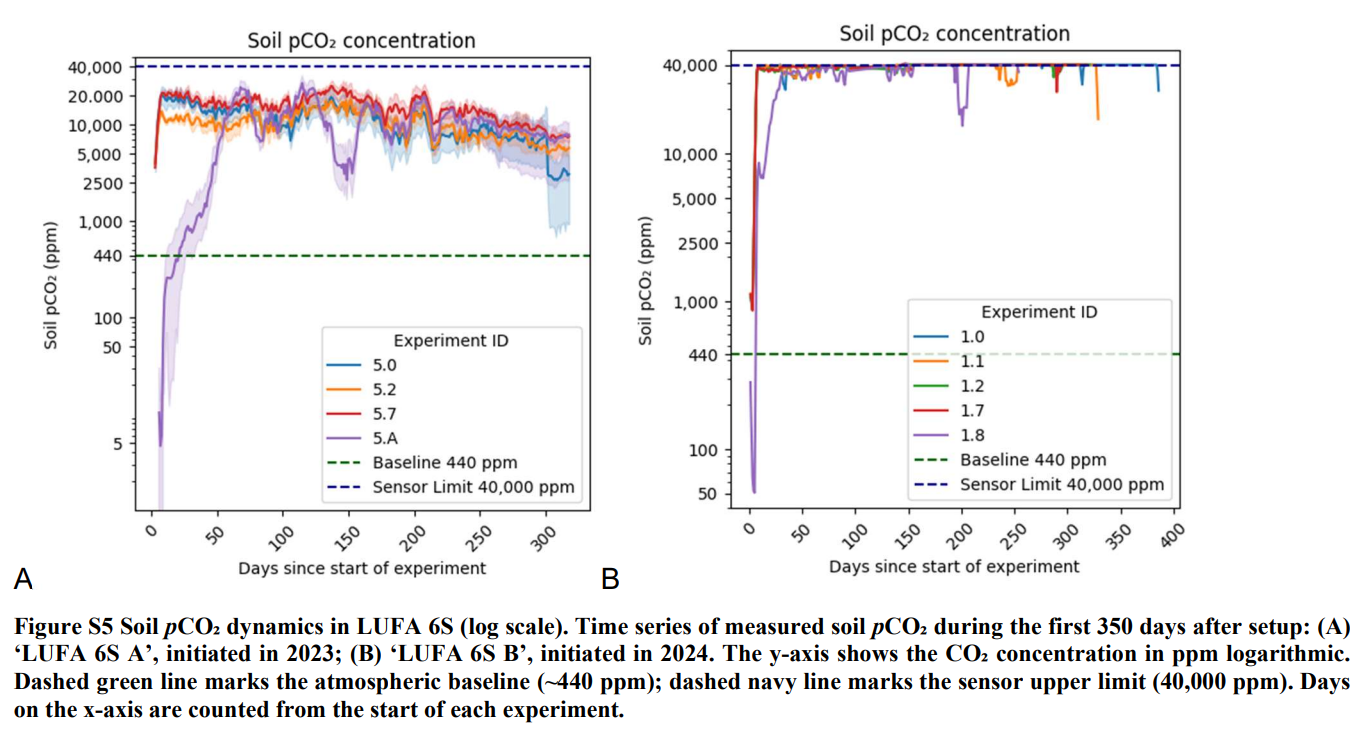

Applied realistic EW application rates (typically 10–40 t/ha equivalent) and grew Lolium perenne (ryegrass) in all pots under warm (>19 °C), well irrigated conditions (> 2,000 mm/year) to speed up weathering.

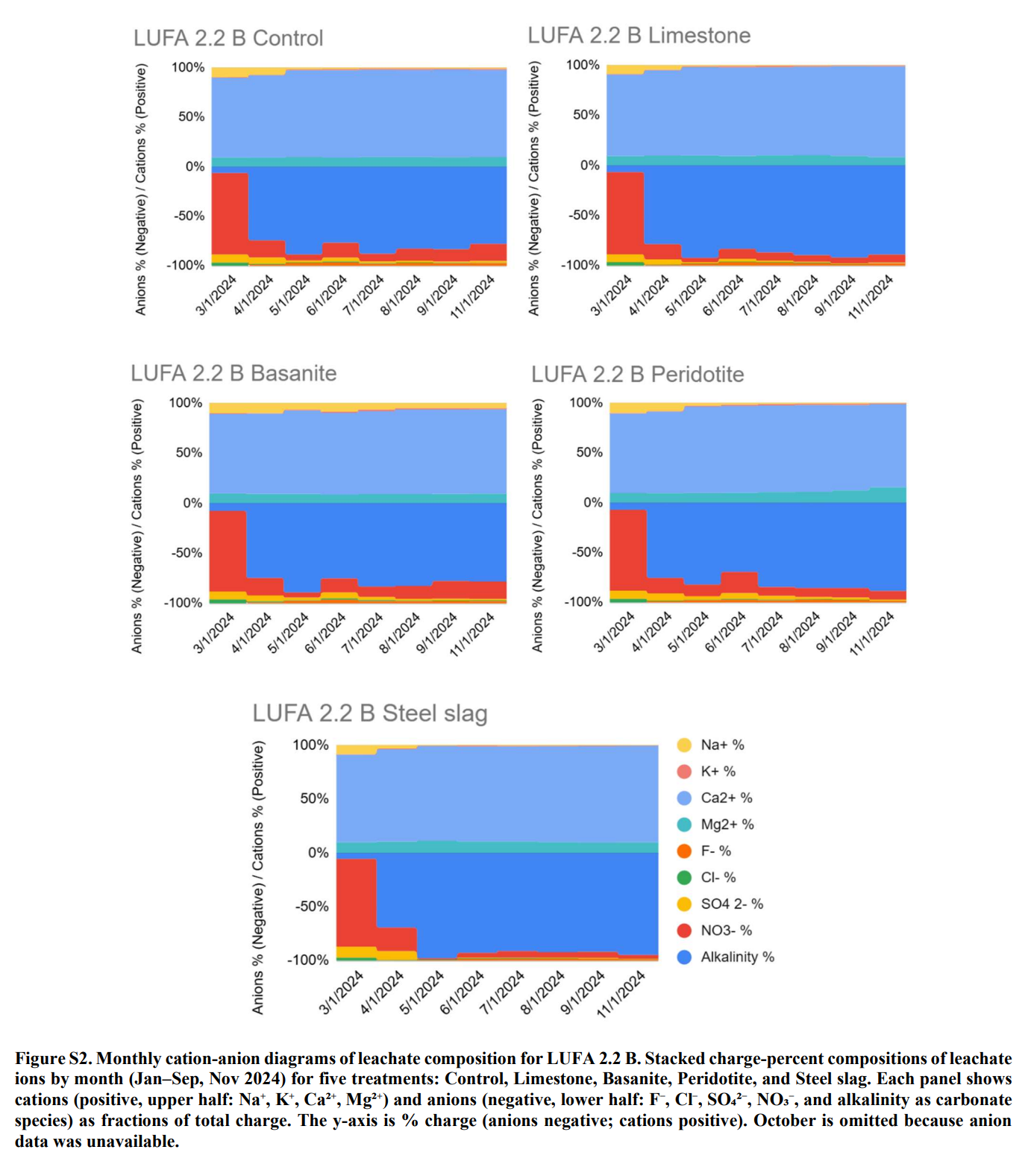

Collected all the leachate water over time and every month measured leachate alkalinity (together with a number of other parameters) to see how much carbon left the soil column as part of the alkalinity.

For a subset of soils, at the end of the 2 year experiment, we performed sequential extractions from these soils to quantify how many base cations (Ca, Mg, Na, K) ended up in the:

exchangeable pool,

carbonate-associated pool,

oxide-bound pool,

and clay pool.

This allows us to compare “carbon that already left the pots as bicarbonate in leachate water” vs. “carbon capture potential that is still stored/delayed in the soil matrix”.

Key results from the new preprint

1. Alkalinity export is highly variable – sometimes even lower than controls

Some rock–soil combinations behaved as expected and increased leachate alkalinity compared to untreated controls. ⇐ This is where we successfully achieved CDR.

Others showed no change – or even less alkalinity export than the control pots. ⇐ This indicates that we may not have removed carbon yet.

This tells us: “Add rock dust → more alkalinity → more CO₂ removal” is not guaranteed. Soil context can completely change the outcome.

2. Clear hierarchy of which materials boost alkalinity

Across all our soils (all from Germany), the strength of the alkalinity signal follows a consistent order:

Steel slag > carbonate‑rich rocks (limestone, carbonate‑rich metabasalt) > peridotite > basanite.

Steel slag (rich in very fast‑dissolving Ca minerals like portlandite) generated the strongest alkalinity increases and the largest cation releases.

Calcite‑bearing materials (limestone, metabasalt with calcite) produced strong early pulses, especially in acidic soils, but their effect dropped off as soil pH rose.

Peridotite (olivine‑rich ultramafic) showed moderate but slower alkalinity gains, mainly in acidic soils.

Basanite (mafic volcanic rock) produced the weakest leachate alkalinity response, often near control levels.

3. Acidic soils export more additional alkalinity; high‑pH, clay‑rich soils trap cations

Soil properties strongly controlled what happened:

In acidic, poorly buffered soils (e.g. LUFA 2.1, LUFA 2.2; pH ~4.6–5.5), EW treatments produced large relative increases in leachate alkalinity, especially for carbonate‑bearing and highly alkaline feedstocks.

In neutral to alkaline soils (e.g. Fürth, LUFA 6S; pH ~7.1–7.7), relative leachate alkalinity responses were often small or even negative compared to controls – despite high absolute alkalinity in some cases.

For high‑pH, clay‑ and carbonate‑rich soils, the data suggests that:

pre‑existing soil carbonates dissolve and re‑precipitate,

cations are exchanged and bound into clay and carbonate phases,

much of the “action” never shows up in leachate.

4. 10–50× more cations stay in the soil than leave in water

The most striking finding comes from the sequential extraction assessing in which pools the cations are retained:

Across the examined German/Central European soils, 10–50 times more cation charge equivalents (Ca, Mg, Na, K) were retained in the soil pools than exported in leachate as alkalinity over the same period.

In an acidic sandy loam, the “best” treatment (steel slag) still retained about 10× more cations in solid pools than were exported in leachate after one year.

In a clay‑rich, slightly alkaline soil, the ratio jumped to about 54× more retention in solid pools than in leachate.

This means that, on the timescale of 1–2 years:

Most of the weathering products are sitting in the soil, not yet moving downwards as bicarbonate.

Whether that already represents long‑term CO₂ storage, a temporary “parking lot”, or predominantly background carbonate cycling is exactly what we still need to figure out.

Why this matters for EW and the CDR industry

A few implications for anyone developing or funding enhanced weathering:

Soil type is as important as rock type. Parameters like pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), soil inorganic carbon, and hydrology (and likely others, too) strongly shape both dissolution and control where cations end up. You can’t just look at the feedstock mineralogy or whole rock geochemistry and assume a certain theoretical CDR rate. The soil characteristics also exert a strong control on CDR, and in-field heterogeneity also needs to be taken into account. Whether soils from other regions of the world (ours are all from Germany) perform fundamentally different needs to be explored, e.g. depleted tropical soils may behave quite differently.

Alkalinity export is only part of the picture. If we only measure bicarbonate in leachate, we likely underestimate total weathering – but we might also misattribute alkalinity coming from pre‑existing soil carbonates rather than from the added rock, leading to overestimation of CDR.

Only a fraction of theoretical CDR seems to be realised quickly. On practical project timescales, the paper suggests that only some of the potential EW CDR shows up as leachate alkalinity; the rest is locked in or delayed by soil pools by processes we don’t yet fully understand.

Models need better data. Current EW models often assume relatively simple dissolution and export behaviour. The greenhouse results show that cation partitioning in soil pools must be included before we can make confident long‑term CDR projections.

Bottom line: EW remains promising, but we don’t yet know enough to predict, for any given field, how much CO₂ will really be removed and for how long.

What’s next

To close these gaps, we are already working on two projects:

We’ve launched a Call for Proposals in which we offered scientists and institutions access to >1,000 soil and biomass samples from the two‑year greenhouse experiment. We have selected our collaborators and we are now working with these teams to extract as much knowledge from these samples as possible.

We’ve started our next generation of greenhouse experiments, twice as large, in early 2025 which involves a lot more soil/rock variations so we can continue to fill up the unknowns.

For everyone watching the EW space: this preprint is a reminder that getting the science right is non‑negotiable. Before we scale EW to gigaton levels, we need to understand how soils really handle rock dust – and that’s exactly what this work, and our ongoing collaborations, aim to deliver.

Read the pre-print of our new paper here:

https://egusphere.copernicus.org/preprints/2025/egusphere-2025-5402/

or